EMPATHY OR ALIENATION?

Leggi la versione in italiano qui

Here I am, in a cyber cafè in the middle of Algerian desert, miles away from the only city within thousands of miles, Tindouf. I'm back in the Saharawi refugee camps, precisely in the middle of the camp that's called “27th February”, as the day in 1976 when these Bedouins who are suffering for a neverending exodus proclaimed their Republic made of sand and wind.

I'm here while outside the sun blinds and inside, next to me, the only customer, the two center managers have their afternoon nap.

It 's the second time I’m visiting this surreal land, a sad geometry of shacks and tents where the Saharawi have been living since 1975, after Morocco had invaded their territory, Western Sahara. I do not know if in 2006, when I came here for the first time, my eyes were looking around with more enchantment, caught by the beautiful red, purple and green traditional clothes of the women and the dark and bewitching eyes of the children. But I’m sure that this time I'm experiencing with violence, almost, the extreme poverty, the dirt, the very little human conditions in which, however, these people are living, studying, believing in the future. Despite their history of blood and their dramatically motionless life.

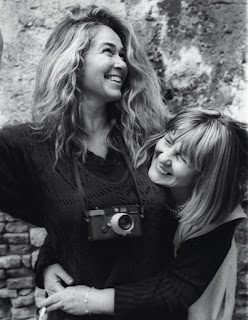

With the photographer Simona Ghizzoni, my consolidated work-mate and my accomplice of looks and feelings, I’ve been doing a reportage on Saharawi women since the beginning of January. We listened to dark stories, intimate and collective tragedies mixed with moments of extreme tenderness. We took the hands of women who broke down in tears in front of our cameras.

We are staying with a Sahrawi family here, sharing all the difficulties that they seem to have metabolized.

Our hostess, Nana, had the chance to live and work elsewhere, in Algiers as in Paris, instead she chose to remain here, in this nebula made of sand. She deeply explained us why, yet I’m still not able to understand it. And since the beginning of our journey I'm thinking on what might be the most right look, the most honest, to tell the stories of these revolutionaries in the desert, condemned to be refugees, still wearing military uniforms, hoping to return to their land even when all attempts of agreement between Morocco and the Polisario Front and Morocco have always failed.

Is more honest an empathy with them or an estrangement? I do not know why, during these hard days, I've come up with the theater dichotomy between Brecht and Stanislawsky: must an actor identify with his character or detach critically from him, to be able to represent him? And so, what is the more correct and right disposition for a journalist? Cutting himself off from what he’s writing, in order to report the facts with more lucidity, or sharing the people’s intimacy to be an authentic witness from the inside?

Ryszard Kapuscinski said that he would never be able to write about someone without sharing with him a piece of life. But here the emotional involvement is likely to overflow in mercy, and I do not want to feel pity, it’s not my job as a journalist, it’s not right. I'm fighting my own battle searching for the meaning and the roads of my job.

Beside me, the guys who run the internet point without ever receiving a salary continue to sleep. While writing these few confused lines, several men came in speaking to me in Spanish and shaking my hand. Here foreign journalists are welcome as friends, women show their wounds on the body in front of the cameras, Islamic religion is deep-rooted but it’s not fundamentalist nor sexist at all.

Tonight we’ll feel cold in our house, probably we won’t have any water. We’ll play with Nizzar, the youngest Nana’son: he’s 3 years old, he never cries and loves to dance when Simona and I listen to Roy Paci’s songs. His only toy is an old broom he uses to have fun in stirring sand outside the fence of his house.

Even the stars, at night, don’t resemble those of our sky.

Commenti

Posta un commento