THE WOMAN IN ORANGE COAT

The woman stops, looks into her eyes. Rests on the opaque glass the open palm of her hand. Patrizia does the same, instinctively. Their hands match.

It is not a glass. It’s a mirror.

The woman has the same Patrizia’s ponytail, the same dark red hair and slanted eyes. She has the face of that young woman who was standing outside the kindergarten, many years ago. A slender figure wearing an orange coat, and crying.

Patrizia remembers everything about that far away day: the swings, the children’s voices, the policemen, the fear of being kidnapped. The only missing piece was the face of that woman in an orange coat, as if memory had drawn a white halo on it.

Now the face is here, in front of her, behind a dirty glass. On a spring day that Patrizia has been waiting for over forty years.

This story would be a perfect subject for a movie. Instead, it is reality. Everything begins in Sicily in the late ‘60s when Vincenzo, a charming policeman of good family, meets Elena, who is only 16. They fall in love and have to hide their relationship, since at that time the internal rule of the police forbade their officers to get married before the age of 31, and Vincenzo is only 23. A child is born, and soon after Elena is pregnant again. Vincenzo can no longer conceal this story: above all, he fears the reaction of his older sister, a woman with a granite morality, the guardian of the honor of their family.

Maybe his sister blames him, maybe she orders him to leave immediately that low-class woman, not to create a scandal and give up the two babies for adoption. He feels overwhelmed, and commits suicide inside the police station, shooting at himself.

It's 1969: Patrizia is one year old and her sister has yet to be born. Their mother disappears.

Today Patrizia is 44. She has a daughter and a good job for a fashion company in Switzerland. Her existential budget is finally active. But she does not forget her childhood in Sicily, growing up with an anaffective and authoritarian aunt, who one day sent her to Rome in a boarding school for policemen's orphans.

About the woman who had given birth to her, Patrizia has ever known one truth only, the one that came out from her aunt’s mouth: her mother did not love her nor her sister so she abandoned them, until that day outside of the kindergarten when she tried to kidnapped them, perhaps to ask the family for some money. And Vincenzo committed suicide because she had tormented him, demanding him to leave the police and marry her.

"Many times I was about to try to find her," says Patrizia, "but I wouldn’t have tolerated one more rejection from her."

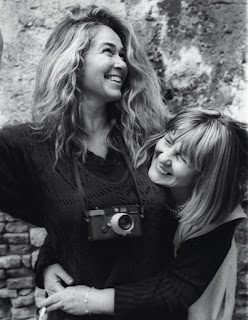

As an adult, in her aunt's house, Patrizia found in an old and dusty suitcase some pictures in black and white: two figures on a meadow, she and her mother, who as a young woman was identical to Patrizia as a young woman, the same expression of joy tinged with slight shadow. "That woman was so similar to me that it was impossible to erase her face from my mind."

Then silence comes again, and it's only everyday life. Until one day in 2003 when Patrizia leafs through a newspaper and remains petrified in front of a news from Comiso, Sicily, in Ragusa province.

There are mugshots of two women. The one on the left reminds her of someone. This woman has confessed she had murdered her partner. Patrizia reads the name: it’s her mother’s name.

“I felt dirty” she says. “I had the blood of a killer flowing in my veins. My sister, however, started looking for our mother, and soon after she discovered that our mother was held in Bologna prison. My sister went to visit her”. ‘It's amazing how much you two are similar," she told me afterwards. And added: ‘She wants to see you, it’s not true that she abandoned us.’ So I wrote my mother a letter, but what can you write to an unknown mother? I started with ‘Dear Ms. Elena’ ... My childhood had been so dark that, talking to her, I was hoping to understand the reasons for all this unhappiness and to find out something about my roots."

Elena immediately replies: “Why did you write ‘Ms. Elena'? I'm your mother.”

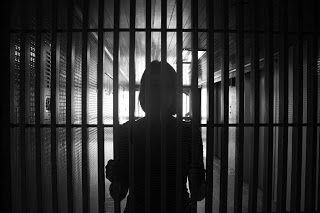

On March 22, 2011, Patrizia wakes up at 5 am and drives for three hours. It's the first time she enters a prison, and it’is traumatic: a bad smell, piled up people waiting for the meeting, the perquisition, the doors that open only when another door has been closed behind you. Three rooms, three steps of control, and each time a neverending wait. A castle of bureaucracy that erases the individual.

In the hall of talks, among squalid plastic tables and loudly echoing voices, there’s a thick and opaque glass: looking at it, you’ll see prisoners coming out from behind. And Elena comes, she’s dull and dowdy. Her penalty in jail will end in 2026.

The two women watch at each otherin silence. They cry. Then Patrizia starts talking about small things: "You know, yesterday I made a move, now I have a new house, it’s big."

"Really? Tell me more".

"There’s a garden."

"How wonderful. I love flowers."

Two hours pass. "We talked as if we had known since always. She eventually asked me: "Will you come back to me?". “Yes, I will.”

Patrizia began leading a life split in two. Her daily life, among beautiful dresses and elegant customers, intercalates with her weekly trip inside the gray of the prison. One meeting after another, the truth comes up dissolving ancient clots and Patrizia sees all her certainties crumble.

She discovers that Elena madly loved her policeman and their babies, but Vincenzo’s family forced her to sign a paper not to recognize the children. She was of poor origins, she was alone, she could not go up against those wealthy and powerful people. But one day she felt she could not stand that separation any longer and went outside the kindergarten just to see her daughters. She was taken to the police station, accused of attempted kidnapping. And she had to put a lid on it. By then, her life rolled down. She got married after a while, had three more children and lived years of hell: her husband used to beat her every time he found her crying because she was thinking about her lost girls and her Vincenzo, whose wonderful memory she’s still in love with today.

So she divorced, started living with another man but he wasn’t better: he forced her to erotic practices with other men. She killed him, blinded with hatred and terror. Her legitimate children are now ashamed of their mother, so she has been abandoned by them and by anyone else. When Patrizia went to her for the first time, Elena was about to be transferred to a psychiatric hospital. “I redid her wardrobe, and the first time I brought her the small Sicilian tomatoes, she ate them one by one like candies. She hadn’t seen them for years.” Patrizia has also managed to transfer Elena to another prison in Milan, Bollate, closer to her and with a better daily life for prisoners. Soon the temporary permissions will come, and then who knows.

Now Elena is able to smile again and, for the first time in her life, she tries to figure out her future.

“I do this for a need of justice” says Patrizia. “She has to serve her sentence, but I'm convinced that her crime is just the end of a cruel and unfair life. No social assistant has never shown up in our house to understand what was going on, and the local Court has never asked any question, as well as the employee who had registered me as a daughter of an unknown mother. There’s plenty of responsibilities in our story. Who ever will refund us for all the pain we suffered?”

She shows me the letters her mother writes her almost every day. There is also a birthday card, a white paper with a blue and pink butterfly drawn by Elena. "Lovely whishes, my daughter. At last I have the chance to tell you: Patrizia, I love you.”

Milan. November 3, 2012

Commenti

Posta un commento